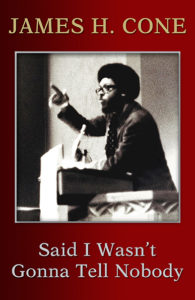

Said I Wasn’t Gonna Tell Nobody

James H. Cone. Said I Wasn’t Gonna Tell Nobody. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2018, 176 pp. $28.00.

Reviewed by Corey Patterson

Few public intellectuals have influenced America’s theological conversation on race more than James H. Cone, the late Bill and Judith Moyers Distinguished Professor of Systematic Theology at Union Theological Seminary. His influential books on the black experience and its theological implications have culminated in his memoir Said I Wasn’t Gonna Tell Nobody, a look into his career as a professor and the struggles he overcame to articulate a new theological perspective within academia. In the book, Cone claims white, European theologians have dominated the study of faith, and he deems it necessary to unpack both his experience and American history to justify the need for voices in black theology.

Cone begins his memoir with an overview of the early influences in his theological career. He details joining an all-white faculty in the midst of the civil rights movement, showing how the groups fighting for social justice and the other professors’ lack of empathy unraveled his previous understanding of God’s relationship with humanity. He cites the Detroit rebellion as one such life-changing event. He says, “The Detroit rebellion deeply troubled me. . . . I could no longer write the same way, following the lead of Europeans and white Americans. I had to find a new way of talking about God that was accountable to black people and their fight for justice” (2).

The nonviolent protests led by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and the Black Power movement headed by Malcolm X inspired Cone in his theological writings. He notes how they disagreed on their approaches to black liberation. For example, Cone claims King “was greatly disturbed about unrest in the cities and the rhetoric of Black Power, which reminded him of the violent language of Malcolm X” (7). Cone believed the two movements could be reconciled, explaining how he “never thought of Black power in terms of violence and hate; rather, it expressed the necessity of black people asserting their dignity in the face of 350 years of white supremacy” (7–8).

Cone goes on to provide ample evidence of the hypocrisy of American and European theologians in the midst of racial inequality. These men interpreted and preached the gospel “in a way that ignores society’s systematic denial of a people’s humanity” (36). He decries the irony of a church that preaches the message of Christ’s love while simultaneously infringing on the rights of black people.

Cone cites theologian Karl Barth as an example of the harm abstract theologizing can have on black communities. Instead of adopting Barth’s “infinite qualitative distinction between God and the human being” (11), Cone uses the suffering of Jesus as an example of God’s identification with the poor and powerless (10). He then analyzes Luke’s gospel declaration of Isaiah 61:1, which speaks of liberation for the poor and oppressed. These examples are used to show how white, European theology had become abstracted from the black community.

In addition to Barth, Cone examines theologians Reinhold Niebuhr and Paul Tillich. Both men taught at Union, and Cone describes them as white theologians who neglected to address black suffering. He says, “Niebuhr had expressed no moral outrage against lynching or segregation, even though he lived during that era” (74). Cone then asked Professor James Luther Adams, “‘Why didn’t Tillich talk about racism in the United States the way he opposed Nazism in Germany?’ Adams said Tillich was asked a similar question and replied that ‘his American audience would reject him’” (74).

This lack of concern over white supremacy in American churches leads to Cone’s rejection of these figures’ theologies as foundational. He argues for a new way of doing theology “from the bottom and not the top,” addressing the plight of black people (10).

Cone goes on to describe the Black Christ, a liberating figure representing Black Power in the gospel. Christ is black, he claims, because “to be black means that your heart, your soul, your mind, and your body are where the dispossessed are” (47). According to Cone, this symbolic identification with the oppressed lies at the heart of the gospel of Jesus Christ.

If the black liberation movement represented Christ’s message, Cone argues, it necessarily means “the white church is the Antichrist” (51). His claim doesn’t refer to individual people; it represents the destructive nature of white supremacy in American churches. He goes on to say “White supremacy . . . is the Antichrist in America because it has killed and crippled tens of millions of black bodies and minds in the modern world. . . . It is found in every aspect of American life, especially churches, seminaries, and theology” (53–54).

Cone continues to make his point by drawing from his father’s experience of oppression and discrimination. He tells the story of Charlie Cone standing up to an all-white school board despite the ever-present threat of lynching from white people. Charlie then filed a lawsuit against the separate but equal ruling in schools, which in reality left black schools with far fewer resources than white schools (57).

Without missing a beat, Cone notes potential criticisms of his views. He specifically highlights scholar Charles H. Long, who saw theology as an unfit tool for the discussion of black liberation, claiming theology was “created by Europeans to dominate and denigrate non-Western peoples” (85). In addition, he cites criticisms from his former student Delores Williams, a womanist theologian who believed black theology failed to speak to women of color, citing the same biblical stories of liberation used in black theology. These included the bondage of Hagar and the subjugation of the Canaanite inhabits following the Exodus, illustrating how liberation could be a “deeply problematic theme, with many ethical and religious contradictions” (120). Cone admits he has no adequate response to these perplexing questions and welcomes them as an opportunity to expand his understanding. He says, “Perplexity keeps me from being too sure of any religious claim I make. Faith needs doubt” (121).

Overall, Cone’s book offers an engaging look at his life using his experiences, history, and logical argumentation to make a compelling case for the necessity of black theology. He is able to unpack deep theological topics by employing the personal language of a close friend telling stories of their life. The memoir serves as a message of hope to people facing issues of racism and discrimination in our world today.

Corey Patterson, BA in Journalism, University of Georgia